The rural digital divide is not an infrastructure problem; it’s a systemic economic and security crisis that actively prevents community participation in the modern world.

- Lack of access leads to billions in annual economic loss and excludes entire communities from high-growth sectors like the digital creative economy.

- It creates critical vulnerabilities in national infrastructure, from telehealth to food production, by hindering the deployment of basic security updates.

Recommendation: Prioritizing policy and funding that empower community-owned fiber networks is the most sustainable path to unlock rural economic potential and ensure national resilience.

In a world that runs on data, high-speed internet is not a luxury; it is the foundational utility of the 21st century. Yet, for millions in rural communities, this utility remains an unaffordable or altogether unavailable dream. The common narrative often frames this digital divide as a simple cost-benefit problem for internet service providers (ISPs). The discussion revolves around the high cost of laying fiber to remote locations, often concluding that more government funding is the sole answer. While crucial, this perspective misses the larger, more alarming reality.

The lack of rural broadband is not merely an inconvenience. It represents a form of systemic exclusion from the entire modern tech ecosystem. It is a persistent “connectivity tax” paid in lost opportunities, diminished economic output, and alarming security vulnerabilities. The true cost isn’t measured in the price of a monthly subscription, but in the inability to access healthcare, educate children, secure a farm, or launch a modern business.

This analysis moves beyond the platitudes. We will not simply repeat that the divide is a problem. Instead, we will deconstruct it. By examining a series of seemingly unrelated technological questions, this article will demonstrate how each one transforms from a simple consumer choice in an urban setting into a high-stakes economic or security challenge in a rural context. Through this lens, we will reveal the true, multifaceted socioeconomic impact of the digital divide and map the strategic imperatives for policymakers and community leaders.

To fully grasp the scope of this challenge, we will dissect it piece by piece. The following sections explore how the lack of fundamental connectivity cripples everything from digital literacy and security to economic development, turning everyday technological hurdles into profound barriers to progress.

Summary: Analyzing the Multifaceted Impact of the Digital Divide

- How to Teach Digital Literacy to Seniors Without Overwhelming Them?

- Server Farms or Aviation: Which Industry Has a Higher Carbon Footprint?

- The Vulnerability in Public Wi-Fi That Exposes 60% of Remote Workers

- How to Boost Your Home Wi-Fi Signal Through Concrete Walls?

- Early Adopter or Late Majority: When Is the Best Time to Buy New Tech?

- How to Automate Your Weekly Reporting Using Zapier or Integromat?

- Creative Hub or Mall: Which Generates More Long-Term Community Value?

- How to Secure Your Smart Home Against Hackers Without IT Knowledge?

How to Teach Digital Literacy to Seniors Without Overwhelming Them?

For most, teaching digital skills to seniors is a matter of patience and simplified user interfaces. In rural America, however, the challenge is compounded by a fundamental infrastructure failure. The question is not just *how* to teach, but how to do so on slow, unreliable, and often-capped internet connections. With nearly 1 in 4 rural Americans still lacking broadband internet access, digital literacy programs must adopt a “low-bandwidth first” mindset. This isn’t just about learning to use a tablet; it’s about learning to navigate a digital world designed for speeds they do not have.

This reality transforms the curriculum. Instead of focusing on video calls, the priority becomes identifying phishing emails that can’t be cross-referenced quickly online. Instead of cloud photo-sharing, it’s about managing offline files and security. The lack of reliable connectivity acts as a risk multiplier, making seniors more vulnerable to scams and misinformation, as they cannot easily verify information or download critical security updates. It also deepens their isolation, as the tools meant to connect them to family and telehealth services become sources of frustration.

In this context, community institutions become vital. As one analysis highlights, libraries have become the de-facto digital education hubs in these regions. They provide not just a connection, but a trusted space where seniors can learn to manage a digital life on the periphery. These programs are forced to innovate, teaching skills like using password managers with offline capabilities and prioritizing text-based communication—skills born of necessity that are entirely foreign to their urban counterparts. It’s a testament to community resilience, but a damning indictment of a national infrastructure policy that leaves the most vulnerable to fend for themselves.

Server Farms or Aviation: Which Industry Has a Higher Carbon Footprint?

While the global tech community debates the environmental impact of data centers, a cruel irony unfolds in rural America. These communities, which possess the open land and renewable energy potential to host the next generation of green data infrastructure, are systematically excluded from the conversation. The reason? They lack the foundational fiber optic networks required to connect these facilities to the global internet. The debate over server farm emissions is a luxury; for rural economies, the core problem is being locked out of the digital economy entirely.

This exclusion has a staggering price tag. The lack of broadband access results in a $47 billion annual economic loss for rural businesses, which are unable to participate in e-commerce, adopt cloud-based tools, or attract remote talent. The conversation about the digital economy’s carbon footprint is moot when a community cannot even be a part of that economy. This is the ultimate “connectivity tax”: being denied the opportunity for economic development while the rest ofthe world moves forward.

However, a new model offers a way forward. Initiatives like the one in Wales exploring edge computing are flipping the script. By placing smaller, decentralized data centers within rural communities, they not only reduce data transit distances (and thus carbon footprint) but also create local, high-tech employment. This transforms rural areas from “connectivity deserts” into potential hubs of green data infrastructure. With the right public-private partnerships focused on building out middle-mile fiber, rural communities could leapfrog from exclusion to becoming integral players in a more sustainable and distributed tech ecosystem.

The Vulnerability in Public Wi-Fi That Exposes 60% of Remote Workers

In urban centers, the security risks of public Wi-Fi are a known inconvenience, often mitigated by using personal hotspots or secure corporate VPNs. In rural areas, this is not a choice but a necessity, and a dangerous one at that. When the local library or café parking lot is the only source of usable internet, it becomes the default access point for everything, including sensitive activities like telehealth. During the COVID-19 crisis, this vulnerability was exposed at scale, as more than 55% of rural residents turned to telehealth, many of whom were forced to use insecure public networks for confidential medical consultations.

This is a direct consequence of the digital divide: the lack of a secure, private connection at home forces residents into a high-risk digital environment. The threat isn’t hypothetical; it’s a daily reality for people managing chronic illnesses, applying for loans, or simply trying to connect with family. The device itself, which should be a lifeline, becomes a liability. This precarious situation creates a two-tiered system of digital security, where geography dictates one’s exposure to cyber threats.

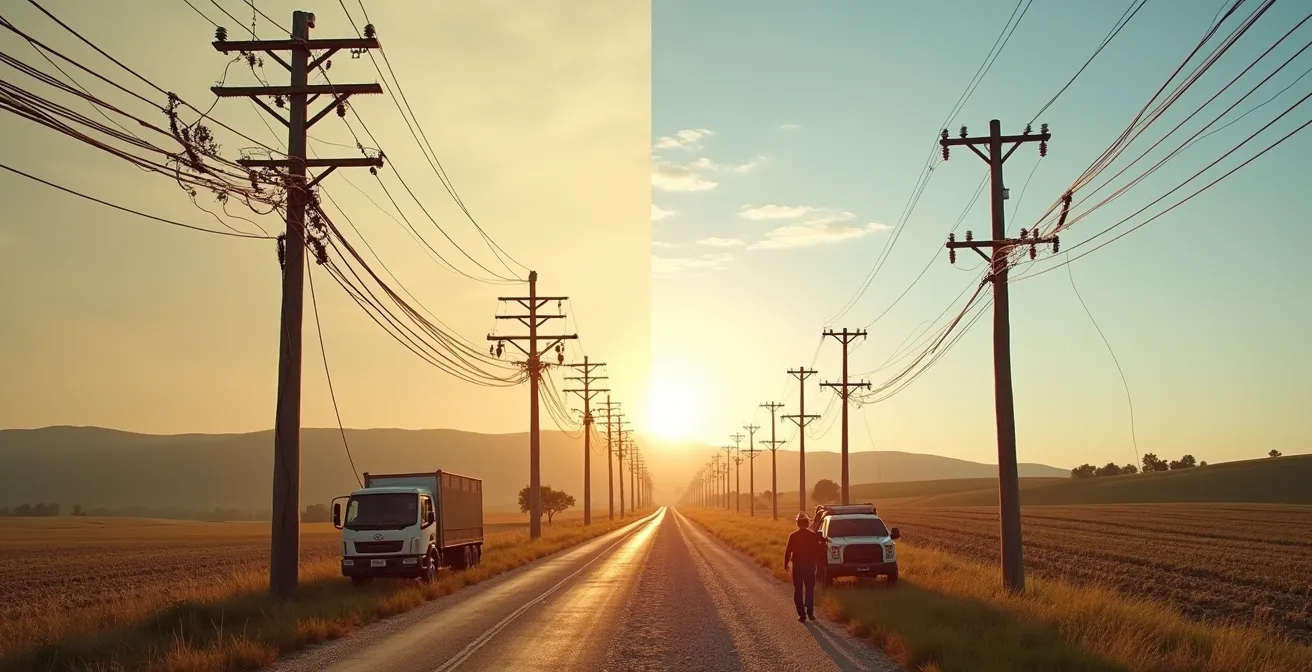

As this image powerfully illustrates, the struggle for connectivity is palpable. It’s a scene of digital desperation, where privacy and security are secondary to the urgent need for a signal. The core issue was perfectly articulated by a leading expert. As John Horrigan of the Benton Institute for Broadband & Society states:

The biggest threat is not a sophisticated hacker, but the inability to download and install critical security updates for these devices due to a slow, capped, or unreliable internet connection.

– John Horrigan, Benton Institute for Broadband & Society

This highlights the ultimate vulnerability: the lack of infrastructure itself is the greatest security risk. It creates a permanent state of digital exposure that no amount of user education can fully mitigate. The only real solution is to eliminate the need for these desperate measures by providing universal, affordable, and secure home broadband.

How to Boost Your Home Wi-Fi Signal Through Concrete Walls?

For the average consumer, boosting a Wi-Fi signal is about buying a mesh router or an extender. It’s a technical tweak to an existing, functional system. For rural communities, the concept of a “signal booster” takes on an entirely different, metaphorical meaning. The problem isn’t a weak signal within the home; it’s the absence of a viable signal coming to the home in the first place. The “concrete walls” they face are not physical but economic and political barriers erected by market failures and policy inaction.

The real “signal boosters” for rural America are not devices, but new ownership and deployment models for infrastructure. Research from the Rural Innovation Initiative reveals a powerful truth: over half of its most innovative rural communities are served by locally-owned broadband networks, not national ISPs. Cities like Wilson, North Carolina (Greenlight municipal fiber) and Independence, Oregon (MINET co-op) show that when communities take control of their digital destiny, they don’t just “boost” a signal; they build a robust, future-proof platform for economic growth.

These community-centric models are fundamentally different from the options offered by incumbent providers. They treat broadband as essential public infrastructure, prioritizing universal access and affordability over quarterly profits. The following table, based on data from policy analyses, starkly compares the available solutions. It shows that while satellite and fixed wireless offer stopgap measures, only models with significant community control, like municipal fiber and co-ops, deliver the speed, sustainability, and local empowerment needed for long-term prosperity.

| Solution Type | Speed Capability | Cost to Deploy | Community Control | Long-term Sustainability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Municipal Fiber | 1 Gbps+ | High initial, low operating | Full local control | Excellent |

| Community Co-ops | 100 Mbps-1 Gbps | Moderate-High | Member-owned | Excellent |

| Fixed Wireless (FWA) | 25-100 Mbps | Moderate | Limited | Good with upgrades |

| Satellite (Starlink) | 50-200 Mbps | Low infrastructure | None | Dependent on provider |

| DSL Enhancement | 10-25 Mbps | Low | None | Poor – outdated |

This data, drawn from an analysis of community broadband investments, makes the case clear. Boosting a signal is a short-term fix. The long-term solution is for policymakers to empower communities to build and own the signal source itself, breaking through the economic walls that have isolated them for decades.

Early Adopter or Late Majority: When Is the Best Time to Buy New Tech?

In the connected world, deciding when to adopt new technology is a strategic choice. Do you pay a premium to be an “early adopter,” or wait for a technology to mature and become a “late majority” user? For rural America, this is not a choice. They are, by default, a forced “late majority” or even “laggards” in technology adoption, not by choice, but because the prerequisite infrastructure is missing. You cannot adopt what you cannot connect.

This forced delay is not a cultural preference; it’s a structural economic problem. As Evan Feinman, the director of the federal BEAD program, bluntly puts it, the reason rural areas are unserved is “a very simple math problem.”

Rural areas make up the bulk of those areas unserved by high-speed internet today. And the reason for that is a very simple math problem.

– Evan Feinman, NTIA BEAD Program Director

The low population density makes the return on investment for private ISPs unattractive, creating a market failure that only significant public investment can correct. The federal government has recognized this with historic funding levels. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act provides $42.45 billion allocated through the BEAD program, a landmark effort to rewire the nation and give rural communities the chance to finally join the tech adoption curve.

This massive investment creates a unique opportunity, as depicted above. Instead of incremental upgrades, rural areas have the chance to leapfrog from obsolete copper lines directly to cutting-edge fiber-optic technology. This isn’t just about catching up; it’s about building an infrastructure that is superior to what many suburban areas currently have. By becoming the new frontier for fiber deployment, rural communities can shift from being forced laggards to becoming the foundation of America’s next-generation digital infrastructure, attracting new businesses and residents seeking world-class connectivity.

How to Automate Your Weekly Reporting Using Zapier or Integromat?

For a modern business, automating tasks with tools like Zapier or Integromat is a standard practice for improving efficiency. This question, however, presupposes the one thing rural businesses cannot take for granted: a stable, high-speed, always-on internet connection. Cloud-based automation tools are rendered useless by intermittent connectivity and restrictive data caps. The inability to adopt these basic efficiency tools places rural businesses at a significant and growing competitive disadvantage.

This is not a minor operational hurdle; it is a fundamental brake on economic growth. While urban competitors are optimizing workflows and freeing up human capital for higher-value tasks, rural entrepreneurs are spending their time on manual processes that could be automated. This “connectivity tax” directly impacts their bottom line, limits their ability to scale, and makes it harder to compete in a national or global marketplace. They are stuck in a pre-automation era, not by choice, but by a lack of infrastructure.

The transformative power of reliable connectivity is not theoretical. A case study of Paul Bunyan Communications’ GigaZone fiber network in Beltrami County, Minnesota, provides clear evidence. After the deployment of fiber, the county saw the number of businesses grow by 12.1%, far outpacing state and national averages. Local businesses were suddenly able to leverage the same cloud-based automation tools as their urban peers, leading to a 7% increase in per-person income between 2020 and 2022. This demonstrates a direct causal link: provide the infrastructure as a prerequisite, and business automation, efficiency, and economic growth will follow.

Creative Hub or Mall: Which Generates More Long-Term Community Value?

The choice between a creative hub and a traditional mall represents a fundamental choice for a community’s economic future: a model of production versus a model of consumption. For too long, rural economies have been pushed toward the latter, their value measured by what they can buy, not what they can create and export. The lack of digital infrastructure has been the primary barrier, making it nearly impossible to build a thriving digital creative economy of programmers, designers, and digital marketers who can work from anywhere.

High-speed internet is the key that unlocks the “creative hub” model. It allows communities to retain and attract talent, reverse decades of brain drain, and build a sustainable economic base that is not dependent on physical retail or manufacturing. A community with gigabit fiber can attract a global clientele for its digital services, generating new wealth rather than simply recirculating existing local capital. The Rural Innovation Initiative corroborates this, finding that communities successfully building these hubs, like Traverse City, Michigan, are those that have invested in locally-owned fiber networks.

Once the infrastructure is in place, the community can begin the strategic work of transforming itself into a magnet for digital talent. This involves a deliberate, multi-step process to build a supportive ecosystem. The following plan outlines the critical steps for any rural community looking to make the leap from a consumption-based economy to a digital production powerhouse.

Action Plan: Transforming Rural Spaces into Digital Hubs

- Form regional broadband coalitions to aggregate demand and create a stronger business case for funding and deployment.

- Develop community-owned “middle-mile” networks that allow multiple local and regional ISPs to offer competitive services.

- Partner with local anchor institutions like libraries and community colleges to create co-working spaces and tech incubators with guaranteed gigabit internet.

- Implement public Wi-Fi zones in downtown and recreational areas to signal to remote workers and digital entrepreneurs that the community is digitally friendly.

- Launch business incubators focused on digital services (e.g., software development, digital marketing, data analysis) that can be exported globally, creating new revenue streams for the community.

By following this roadmap, rural communities can shift their economic destiny. They can choose to become vibrant centers of creation, generating far more long-term community value than any retail mall ever could.

Key Takeaways

- The rural digital divide is an economic and security crisis, not just an infrastructure gap, costing billions in lost productivity and opportunity.

- Lack of reliable broadband creates systemic security vulnerabilities by preventing critical updates for healthcare, agriculture, and smart home technologies.

- Community-owned network models (municipal and co-op) have proven to be the most effective solution for driving adoption, economic growth, and long-term sustainability.

How to Secure Your Smart Home Against Hackers Without IT Knowledge?

For the average homeowner, securing a smart home involves simple steps: using strong passwords, enabling two-factor authentication, and keeping firmware updated. This advice, however, is dangerously incomplete in a rural context. The most critical step—regularly downloading and installing security updates—becomes a significant challenge, if not an impossibility, on a slow, unreliable, or data-capped internet connection. This vulnerability extends beyond smart speakers and into the critical domain of smart farming and agricultural IoT.

In modern agriculture, IoT sensors that monitor soil moisture, control irrigation, and guide autonomous tractors are essential for efficiency and yield. These devices are part of a farm’s critical infrastructure. When they cannot be reliably updated, they become a glaring security hole, making a nation’s food supply vulnerable to disruption by malicious actors. The problem is not a lack of IT knowledge among farmers; it is a lack of the fundamental connectivity required to maintain a secure digital operation. This is the ultimate risk multiplier, where a simple firmware update stands between a normal harvest and a potential agricultural crisis.

The fragility of this system is being exacerbated by policy failures. The recent end of the Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP), for instance, has immediate security implications. As the FCC reports, 3.4 million rural households lost their internet subsidies, forcing many to downgrade or disconnect. Each disconnected household is another unpatched router, another vulnerable device, and another potential entry point into our interconnected world. The issue of smart home security in rural areas is, therefore, inseparable from the economics of access and the policy of affordability.

The evidence is clear: solving the rural digital divide is an economic and national security imperative. To build a resilient and equitable nation, the essential next step for policymakers and community leaders is to champion policies and funding mechanisms that empower local communities to build, own, and operate their digital future.