Contrary to popular belief, the reason you’re not losing weight isn’t a lack of willpower, but your brain misinterpreting visual cues from oversized plates and portions.

- Restaurant and home portion sizes have ballooned, silently adding hundreds of uncounted calories to “normal” meals.

- Even “healthy” foods like avocado and olive oil are incredibly calorie-dense, and over-consuming them is a common mistake.

Recommendation: The most effective strategy is to master visual calibration—training your eyes to recognize appropriate portion sizes, turning subconscious overeating into a conscious, controlled choice.

You’re doing everything right. You diligently order the grilled salmon instead of the burger, choose the side salad over the fries, and sip water while your friends have cocktails. You feel you’re in a perfect calorie deficit, but the numbers on the scale refuse to budge. This frustrating paradox is a common experience, and it’s rarely a matter of willpower. The culprit is often an invisible force at play during every meal: portion distortion.

For decades, standard serving sizes in restaurants and at home have quietly expanded. What we now perceive as a “normal” plate of food is often two or three times the recommended serving. While common advice focuses on what to eat, it often ignores the more critical question of how much. We count calories, avoid carbs, and track macros, but we fail to account for the psychological and physiological traps that our modern food environment sets for us.

The key to breaking this cycle isn’t a more restrictive diet; it’s understanding the cognitive biases that trick your brain and the hormonal signals your body uses to communicate fullness. This article moves beyond generic tips and dives into the behavioral psychology of eating. We’ll explore why your brain is easily fooled by plate size, why your body has a “hormonal lag” in feeling full, and why even the healthiest foods can sabotage your progress if portioned incorrectly.

By the end, you’ll be equipped with practical, psychology-backed strategies to recalibrate your perception of portion sizes. You’ll learn to turn mindless consumption into mindful eating, empowering you to finally take control of your calorie deficit and achieve the results you’ve been working so hard for.

To navigate this complex topic, we’ve broken it down into key psychological and physiological challenges. This guide will walk you through each one, providing the “why” behind the problem and the “how” for the solution, helping you build a new, more effective relationship with food.

Summary: Deconstructing the Hidden Saboteurs of Your Calorie Deficit

- How to Measure Pasta Portions Without a Scale Using Your Hand?

- The “Small Plate” Trick That Reduces Consumption by 20%

- The Mistake of Eating Unlimited “Healthy” Fats Like Avocado

- How to Portion Leftovers Immediately to Avoid Second Helpings?

- Why Must You Wait 20 Minutes Before Going for Seconds?

- Why Does Your Body Prefer Burning Sugar Over Fat?

- Fight or Flight: How Does Stress Change Your Metabolism?

- Why Does Dehydration Cause “Fake Hunger” Pangs in the Afternoon?

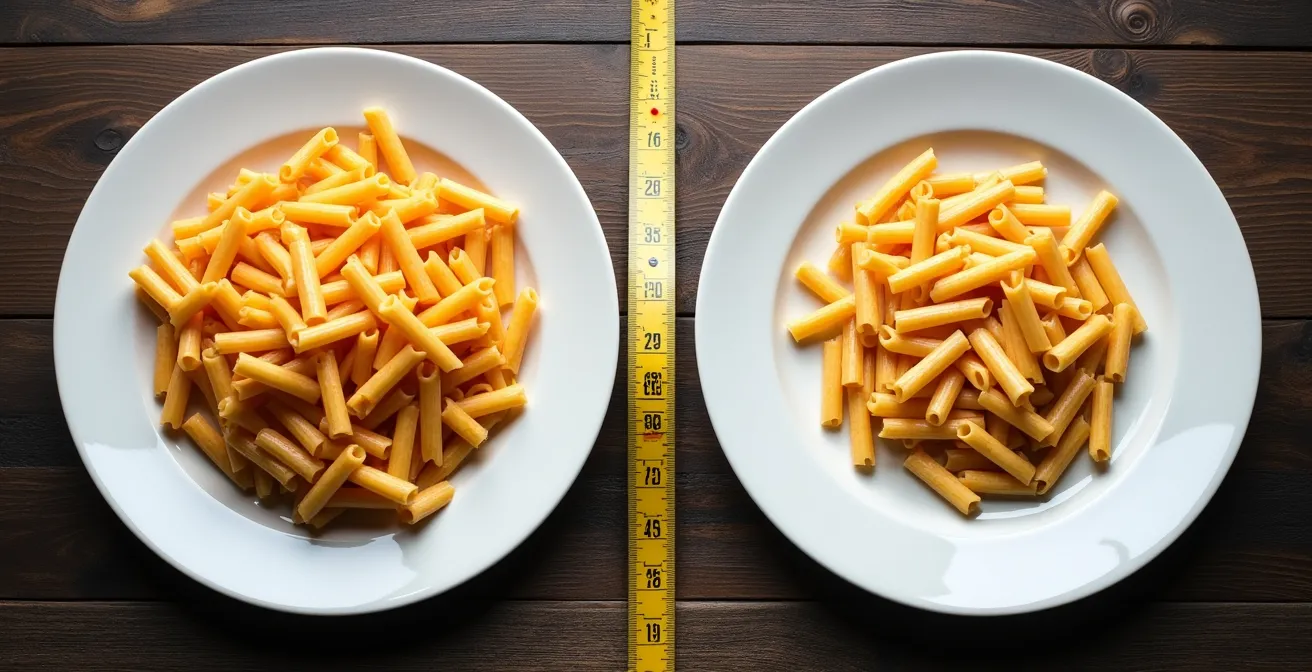

How to Measure Pasta Portions Without a Scale Using Your Hand?

One of the biggest hurdles in managing a calorie deficit is the phenomenon of portion distortion. Over the past few decades, what we consider a “normal” serving has expanded dramatically. Studies show that eating the same foods as 20 years ago but in today’s portion sizes would result in consuming hundreds, if not thousands, of extra calories. This makes accurately gauging food intake without a scale seem impossible, especially with amorphous foods like pasta. However, you carry a surprisingly accurate measurement tool with you at all times: your hand.

Learning to use your hand for visual calibration is a fundamental skill for anyone trying to manage their weight without the tediousness of constant measuring. This method is not only practical for dining out but also helps retrain your brain to recognize appropriate serving sizes instinctively. The goal is to build an internal reference system that works anywhere, anytime.

As the image demonstrates, the contours and size of your hand provide reliable portion estimates. For carbohydrates like pasta or rice, a single cupped hand represents a standard serving, roughly equivalent to 1/2 or 2/3 of a cup. For protein sources like chicken or fish, the size of your palm (excluding fingers) corresponds to about 3-4 ounces. A fist is a good measure for a cup of vegetables, and the length of your thumb approximates a tablespoon of dense fats like oil or nut butter. This system naturally scales with your body size, as larger individuals with higher caloric needs typically have larger hands.

The “Small Plate” Trick That Reduces Consumption by 20%

The advice to “use a smaller plate” is common, but few understand the powerful psychological principle behind it. This isn’t just a simple trick; it’s a way to counteract a well-documented cognitive bias known as the Delboeuf Illusion. This optical illusion causes us to perceive the same amount of food as smaller when placed on a large plate and larger when on a small plate. Your brain judges quantity relative to the container, not in absolute terms.

When a restaurant serves a meal on an oversized 12-inch plate, the food can look sparse, prompting you to feel unsatisfied or believe the portion is smaller than it truly is. Conversely, that same portion on a 9-inch plate appears abundant and filling. Your brain is tricked into feeling more satisfied with less food. This is not a failure of willpower; it is a predictable quirk of human perception that restaurants, whether intentionally or not, exploit with their large dinnerware.

Research on this phenomenon is clear and compelling. A pivotal study on the Delboeuf illusion confirmed how dinnerware size creates biases that lead people to over-serve on large plates. The findings suggest that reducing plate diameter can lead to a significant, automatic reduction in the amount of food consumed—often around 20%—without the person feeling deprived. The study also noted that while education about the illusion does little to stop it, changing the color of the plate to contrast with the food can help mitigate the effect. By simply choosing smaller plates at home or mentally sectioning off your plate in a restaurant, you can leverage this illusion in your favor.

The Mistake of Eating Unlimited “Healthy” Fats Like Avocado

A common dieting pitfall is the “health halo” effect, where we assume that because a food is “healthy,” we can eat it in unlimited quantities. Foods like avocados, nuts, and olive oil are nutritionally beneficial, packed with monounsaturated fats and vitamins. However, they are also extremely calorie-dense. This means a very small volume of these foods contains a large number of calories. Ignoring portion sizes for these items is one of the fastest ways to unknowingly erase a calorie deficit.

Just a small, consistent overconsumption can have a massive impact over time. For example, consuming just 300 extra calories daily can lead to a weight gain of nearly 30 pounds in a single year. That’s the equivalent of adding two tablespoons of olive oil and half an avocado to your daily salad without accounting for them. The problem isn’t the food itself, but the disconnect between its perceived healthiness and its actual caloric weight.

The following table provides a stark visual of this concept, showing how much of each food you get for 100 calories. It highlights the vast difference in volume between calorie-dense fats and high-volume, low-calorie vegetables.

| Food Item | Calories per 100g | Volume for 100 Calories |

|---|---|---|

| Avocado | 160 | 62.5g (1/4 avocado) |

| Broccoli | 34 | 294g (3 cups) |

| Olive Oil | 884 | 11g (1 tablespoon) |

| Chicken Breast | 165 | 61g (2 oz) |

This visual discrepancy is where dieters often get into trouble. You could eat nearly three cups of broccoli for the same number of calories as a single tablespoon of olive oil. By learning to respect the calorie density of healthy fats and practicing strict portion control with them, you protect your calorie deficit from these hidden additions.

How to Portion Leftovers Immediately to Avoid Second Helpings?

The decision to stop eating is rarely made when your stomach is full; it’s made when the plate is empty. This is a critical psychological insight. We are conditioned to “clean our plates,” and the visual cue of a finished meal signals the end of eating. When dining out, where portions are enormous, this instinct works directly against our goals. The solution is not to muster more willpower in the moment, but to use a strategy of pre-commitment.

Pre-commitment involves making a choice in advance, before you are faced with temptation. As Registered Dietitian Skylar Weir notes, our ability to estimate intake is notoriously poor. A review from UCHealth highlights that most people underestimate how much they eat by 20-50%, especially with high-calorie restaurant meals. By asking for a to-go container the moment your food arrives, you change the environment and the default behavior. You are no longer facing a mountain of food you must conquer; you are facing a manageable meal and a pre-portioned lunch for tomorrow.

This simple action shifts the “finish line” from an empty plate to the pre-portioned section you’ve designated for your current meal. It removes the temptation for “just one more bite” and prevents mindless grazing that occurs when food remains in front of you. Implementing this strategy consistently is a powerful behavioral tool for managing restaurant meals.

Your Action Plan: The Pre-Portioning Strategy

- Ask for a to-go container when your meal arrives, not after you’ve started eating.

- Immediately divide your meal in half, placing one portion directly into the container.

- Close the container and set it aside, ideally out of sight, to remove the visual temptation.

- Focus on mindfully enjoying the portion remaining on your plate, free from the pressure to finish everything.

- At home, store leftovers in individual, meal-sized containers to prevent creating another oversized portion later.

Why Must You Wait 20 Minutes Before Going for Seconds?

The feeling of “fullness” is more complex than a simple sensation in your stomach. It’s a two-part process involving both physical and hormonal signals, and the delay between them is a critical window where overeating often occurs. This is what can be termed the “hormonal lag.” Immediately after you eat, your stomach stretches, activating nerve receptors that send a rapid, initial signal of fullness to your brain. This is physical satiety. However, this feeling is temporary and can be misleading.

True, lasting satiety comes from a hormone called leptin. After you consume food, particularly fats and proteins, your fat cells release leptin into your bloodstream. It then travels to your brain’s hypothalamus, the control center for appetite, and signals that you have sufficient energy. This powerful hormonal message is what truly turns off your hunger drive. The catch? This entire process takes approximately 20 minutes. If you rush to get a second helping after only 5 or 10 minutes, you are making an eating decision based only on stomach stretch, before the “I’m truly full” hormone has even arrived at its destination.

Instituting a mandatory 20-minute waiting period before considering a second helping is a behavioral rule that allows your physiology to catch up with your food intake. During this time, you can aid the process. Engaging in conversation, clearing the table, or drinking a full glass of water can help. As some research suggests, drinking water up to 30 minutes before a meal can increase feelings of fullness and has been associated with lower calorie intake. This waiting period isn’t about restriction; it’s about giving your body the time it needs to send an accurate report on its energy status.

Why Does Your Body Prefer Burning Sugar Over Fat?

Your body is an efficiency machine, always looking for the quickest and easiest source of energy. In the metabolic world, that source is glucose (sugar). When you consume carbohydrates, they are broken down into glucose, which enters your bloodstream and is readily available for your cells to use as fuel. Burning fat, on the other hand, is a more complex and slower process. Your body keeps fat stores as a reliable, long-term energy reserve, like a savings account, while it treats glucose as cash on hand.

This metabolic preference is why oversized, carbohydrate-heavy restaurant meals are particularly detrimental to a calorie deficit. When you consume a large portion of pasta, bread, or a sugary dessert, you provide your body with a massive, immediate influx of its favorite fuel. It will work to burn that glucose first, and any fat you consumed with that meal (or that was already in your system) is put on the back burner. If the glucose intake exceeds your immediate energy needs, your body will convert the excess into glycogen for short-term storage and, ultimately, into more body fat for long-term storage.

The fundamental equation of weight management remains simple, as the research team at Nerd Fitness explains. In their guide, they state, ” When you consume more calories than you burn, your body tends to store those extra calories as fat. When you burn more calories than you consume, your body will pull from fat stores for energy.” The problem with modern portion sizes is that they make it incredibly easy to land in the first scenario, constantly providing the body with easy-to-burn sugar and never forcing it to tap into its fat reserves.

Fight or Flight: How Does Stress Change Your Metabolism?

Your metabolism isn’t just a static calorie-burning engine; it’s deeply interconnected with your nervous system, especially your stress response. When you perceive stress—whether it’s a looming work deadline or the social pressure of a group dinner—your body activates its “fight or flight” mode, also known as the sympathetic nervous system. This triggers a cascade of hormonal changes, most notably the release of cortisol.

While cortisol is essential for short-term survival, chronic low-level stress keeps cortisol levels elevated, which can wreak havoc on your eating behaviors and metabolism. Cortisol directly increases your appetite, and it specifically drives cravings for high-fat, high-sugar, “comfort” foods. It’s an evolutionary mechanism designed to make you seek out quick, dense energy in a crisis. In a modern context, this means the stress of a noisy, crowded restaurant or anxiety about making “correct” food choices can physically make you crave the very foods you’re trying to avoid.

The restaurant environment itself can be a significant source of stress. The pressure to indulge with friends, the presence of tempting menus, and the anxiety of navigating dietary goals in a social setting can all contribute to this response. To counter this, you can employ strategies to activate your “rest and digest” mode (the parasympathetic nervous system). Simple actions like taking a few deep breaths before ordering, reviewing the menu online beforehand to reduce decision fatigue, and choosing a quieter table can lower your cortisol levels and help you make more conscious, less reactive food choices.

Key Takeaways

- Portion distortion is a cognitive bias; use smaller plates and your hand as a guide to visually recalibrate your brain.

- “Healthy” does not mean “low-calorie.” Be mindful of the high calorie density of fats like oils, nuts, and avocado.

- Leverage the 20-minute hormonal lag by waiting before taking seconds to allow your satiety hormone, leptin, to work.

Why Does Dehydration Cause “Fake Hunger” Pangs in the Afternoon?

One of the most commonly overlooked saboteurs of a calorie deficit is simple dehydration. The body’s signals for thirst and hunger are surprisingly easy to confuse, primarily because they are both regulated by the same part of the brain: the hypothalamus. When you haven’t had enough water, the hypothalamus can send out signals that your brain misinterprets as a need for food, leading you to reach for a snack when all your body really needed was a glass of water.

This phenomenon is often most pronounced in the afternoon. You’ve been busy at work, you haven’t been sipping water consistently, and suddenly you’re hit with a craving for something salty or sweet. Before acting on this “hunger,” the most effective first step is to drink a full 8-12 ounce glass of water and wait 15 minutes. More often than not, you’ll find the hunger pangs subside completely. As the nutrition experts at BistroMD note, “Dehydration can be mistaken for hunger, which may lead to food intake when the body is actually craving water.”

Making hydration a proactive part of your day is a simple but powerful behavioral strategy. Keeping a water bottle on your desk, setting reminders on your phone, or starting your day with a large glass of water can prevent these “fake hunger” signals from ever arising. It’s a foundational layer of self-regulation that supports all your other efforts. By addressing your body’s need for water first, you ensure that when you do feel hungry, the signal is genuine, allowing for a more accurate response to your body’s true energy needs.

By understanding these psychological and physiological drivers, you can shift from a reactive dieter to a proactive architect of your eating habits. Start today by implementing just one of these strategies—whether it’s waiting 20 minutes, pre-portioning leftovers, or simply drinking a glass of water before a meal—to begin taking conscious control of your calorie deficit.

Frequently Asked Questions About Portion Control and Satiety

What can I do during the 20-minute waiting period?

Engage in conversation, help clear the table, drink a full glass of water, or take a short walk to distract from the urge to eat more. The goal is to shift your focus away from food and allow your body’s hormonal signals time to register in your brain.

Why do I still feel hungry immediately after eating?

Stomach stretch receptors provide an immediate but temporary signal of fullness. True, lasting hormonal satiety, driven by the hormone leptin, takes about 20 minutes to fully register in your brain. This delay is why you can feel “stuffed” yet still want more in the short term.